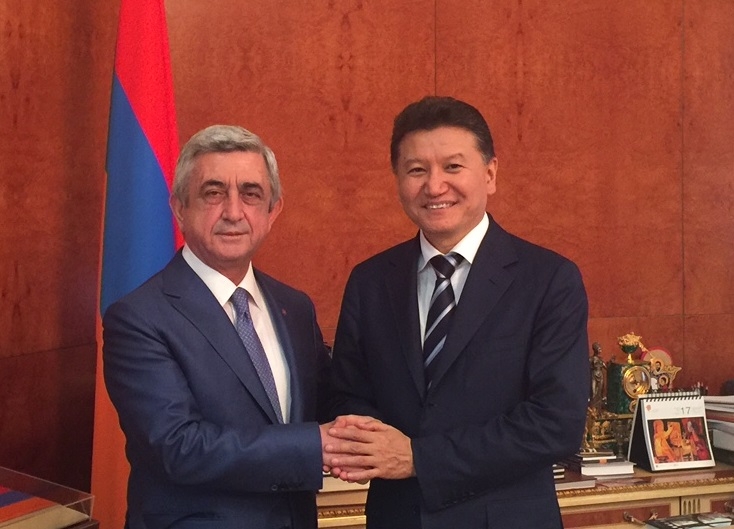

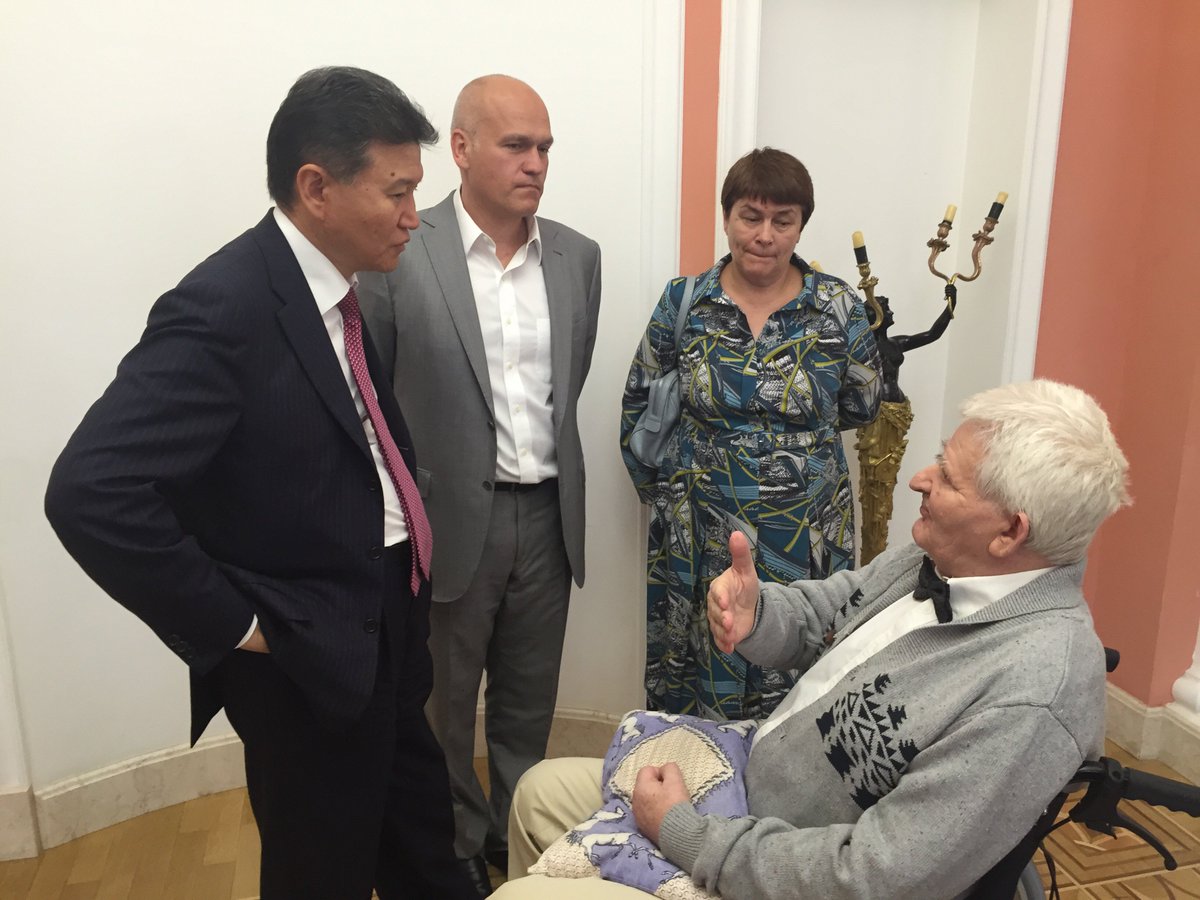

The first thing that catches the eye is that retired Ilyumzhinov never said, “I am tired, so I leave”. He made no statements like "I did everything I could." On the contrary, he had energy in abundance that he proved by visiting annually up to hundreds of countries as President of the International Chess Federation (FIDE).

Ilyumzhinov resigned in October 2010, and in January of the same year Vladimir Putin, then the acting head of the Russian Government, said about his work: “Despite the crisis of 2009, the Republic of Kalmykia showed a positive trend in the growth of industrial production, in housing and in improving of the labour market. There are still many problems, but it is encouraging that the dynamics are positive. ”

The compatriots were much more emotional, summing up the work of Ilyumzhinov in such words: “For 17 years, significant changes have taken place in Kalmykia. Kirsan Ilyumzhinov directed all his energy towards improving people's lives. Recall gasification of the steppe republic, construction of the Chess City and the largest khurul in Europe!” They also recalled new midwife centres in the villages, systematic work on the revival of animal husbandry, and much more.

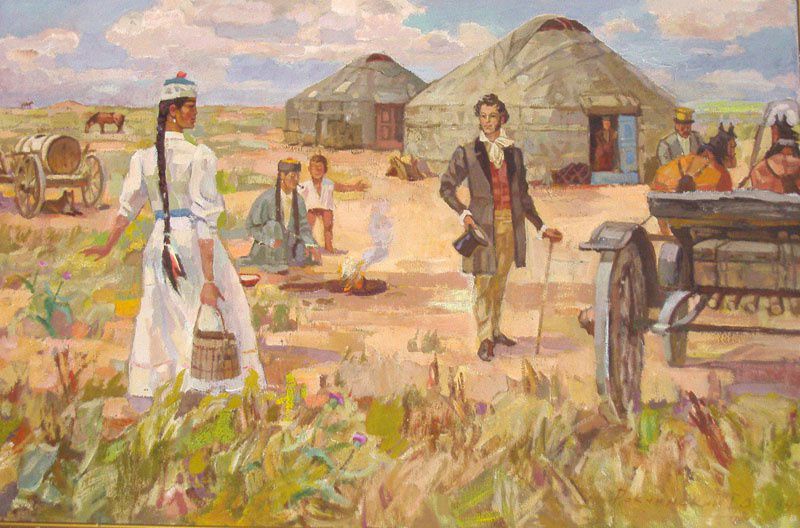

However, it would be wise to remember what Kalmykia was by the end of the twentieth century. Of course, Kalmykia received some funding, but that was done mostly for the record because of ineffective inertia within the Soviet bureaucracy. The local authorities tried not to bother Moscow and did not care for the true needs of their people.

As a result, when Kirsan Ilyumzhinov was elected President of Kalmykia in the spring of 1993, the republic was, if not in ruins, then close to that. Never mention the lack of gas, which was common even for the regional centres of larger and richer regions of Russia. Never mention roads that represent, as you know, one of the two eternal problems of our country (there were practically no roads in Kalmykia). Suffice to say that out of the famous herd of small cattle, only 470 thousand sheep remained. It is not bad for a large collective farm but practically nothing for a republic.

It is better not to recall the state of culture, education, and spirituality: there was neither a theatre nor a worthy museum nor a school with education in the native language. Religious needs in this Buddhist region (it’s still hard to bear the burden of earthly existence without God) were “served” by the one and only small Orthodox (!) Church.

And then there was perestroika. No wonder that the first Russian president, Boris Yeltsin, called for “Taking as much sovereignty as one can stomach”. It was not so much a generous offer, but rather recognition of major financial issues and problems at the federal level. However, the big party and economic bosses could not adjust, and the simple residents of Kalmykia saw this perfectly well.

At that time, some of them remembered the young manager Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, who had successfully developed his business in Moscow since the beginning of perestroika. It wasn’t a spontaneous decision. By that time, he had already defended interests of his fellow citizens for three years as a deputy to the Supreme Soviets of Russia and the USSR.

We will not talk about all the vicissitudes of the election campaign of 1993 in Kalmykia. Much has been written about it, including what was written by Kirsan Nikolayevich himself. We will only note that all his opponents were very serious local “political heavyweights”. Nevertheless, he won with a huge margin, gaining 65.37% of the vote and thus becoming the youngest of the regional leaders of Russia.

According to Ilyumzhinov, his fellow citizens had such confidence because they believed in his ability to take responsibility. The same thing happened in other regions - Mintimer Shaimiev won in Tatarstan, Murtaza Rakhimov in Bashkiria, Eduard Rossel in Urals, and Mikhail Nikolaev in Yakutia: no matter how ambiguous they may seem, they were united by caring for their native land and willingness to take risks for the sake of residents’ well-being.

Meanwhile, the first decree of Ilyumzhinov as President of Kalmykia was not about the economy but about ... chess! Detractors laughed: wooden pieces instead of bread! Here is your president! However, Ilyumzhinov was looking to the future: students’ performance increased by an average of forty percent after introduction of chess in local schools. Moreover, this was the key to develop competitiveness.

However, man does not live by chess alone. Ilyumzhinov made officials pay attention to other forms of youth leisure. Despite all obstacles, chess circles and sections were opened in schools, and sometimes in any suitable outbuildings. This allowed to reduce criminal tensions by attracting young people.

Incidentally, since we touched upon crime, one should recall few things. Our fellow citizens, who survived the dashing nineties, remember how buying the bread in a nearby store became an adventure. Drug addicts and alcoholics, ready to do anything for the money for another dose, were commonplace. Moreover, on your way back, you could find your home broken into.

Criminality was dealt with relatively quickly in Kalmykia - this was one of Ilyumzhinov’s main demands on local security officials. There is a historical anecdote in the republic: once Ilyumzhinov publicly mentioned that it would be nice to return to the traditions of ancestors who cut off the hands of thieves. This was said to be a joke, but soon a delegation of elders came to the president with a proposal to start with only fingers. So high was the belief that if Ilyumzhinov said something, he would do it. However, more importantly, criminality believed this threat. Many mobsters have chosen to go to other regions or keep a low profile.

(to be continued)

Kirsan Ilyumzhinov happened to lead Kalmykia in the most difficult period of the modern history of Russia. Now it becomes clear that this time was nearly the best in the steppe republic’s life.

Kirsan Ilyumzhinov happened to lead Kalmykia in the most difficult period of the modern history of Russia. Now it becomes clear that this time was nearly the best in the steppe republic’s life.