"A ceremonial funeral, huh?... What the hell is all this solemnity for? After all he was not a beast to rejoice in his death. Those big shots aren't man-eaters, are they?"

After the army I returned to my old factory only to find that nothing had changed there. I worked as a fitter. It was not only the plant which had not changed; there had been no change in my home city or the Kalmyk republic either. Only one thing had changed: me. l was a different man now. In provincial towns life flows at a slow and unhurried pace. After the time spent in the army I felt as though the city of my childhood was fencing me in.

On one occasion I stumbled upon a typescript of the Kalmyk horoscope. In those days this was tantamount to dissident literature, something almost illegal. It was impossible to find published horoscopes now. Like anyone raised under the oppressive Soviet system, who was lucky enough to get his hands on a semi-legal treatise, I did not throw it away or hand it in to the KGB or the local party Committee. Instead I began to study it thoroughly. Most Soviet citizens realized during their high-school days that any individual who is severely criticized by the official press must be a good and decent person and, if something is forbidden, it means that there is truth in it.

As I have already mentioned I was born in 1962, the year of the Tiger. "And the days will come when the souls of the believers will dwindle to the size of an elbow and man himself will become as faint-hearted and timorous as a hare, and the Buddha's great and pure teaching will grow dim. Then the people will indulge in drinking and greed and the worthless will rule the world. Then he will emerge, the Tiger, the powerful protector of the Earth and the Lord of all oriental lands. The Earth will be shaken by his horrible roar and the worthless and miserable rulers will scatter in fear, there will be no more lies and the minds of the stray will regain clarity. Those born in the Year of the Tiger will be summoned to govern then and bring nobility to their people."

After reading this l thought to myself that perhaps in faraway Simbirsk or in Moscow such a man had already been born. Perhaps he was even my age and would set our upside down world to rights. What might such a man be thinking now, I wondered. Maybe be was twelve years my junior or senior. After all, the Year of the Tiger is repeated every twelve years according to the Buddhist calendar. How would he begin to implement future changes? And bow would they come about?

That same year I had an acute presentiment of change. Something was brewing in the air at that time. lt was becoming harder and harder to breathe as though a thunderstorm was approaching . The country was longing for the air of freedom. With every nerve and fiber of my being I felt that somewhere, at the other end of the Soviet empire, a future reformer was living, thinking and already beginning to act. What would his first steps be? Would he start out with political or economic reforms? Or perhaps both? Which was more important?

In order to be able to answer these questions I began to study text-books on economics and politics, to collect statistics and read the newspapers closely. These new areas of interest proved very helpful during my entrance examinations to the Moscow Foreign Relations Institute (FRI), the most prestigious and inaccessible higher educational institution in the USSR.

I had never dreamed of becoming a diplomat. The terms "diplomat" and "ambassador" belonged to a different, more beautiful world, the unobtainable world of the Soviet elite which I, a mere fitter from a small-town factory, had only the vaguest notion of.

The FRI was rumored to be a school for the chosen few, the offspring of people with top-level family connections. So, in spite of all the unadventurous spirits surrounding me, or perhaps in order to prove to myself that I was worth something, I applied for the prestigious and virtually inaccessible Japanese department. My chances were very slim, but I had nothing to lose. Besides I was desperate to find out if I could pass the test and be admitted to the institute.

"You haven't learned anything in either the army or the factory," my parents told me when I announced my decision to them. "It is time you stopped trying to catch pie in the sky. Come down to earth."

"Whatever for? After all, Slava has managed to enter the institute, hasn't he?" I said.

"How can you compare yourself with Slava? His is an altogether different case!"

That was quite a support! As a matter of fact my parents have always treated me with some caution. And also one had to appreciate the mores of a small provincial town. Here everyone knows everyone else, rumors spread with lightning speed and became overgrown with invention and opinion. In short, my parents did not want people to laugh at me behind my back and wag their fingers at me saying: "Just look at him! Can you picture that wretched fitter as a diplomat?" As for me, I was not in the least upset by their chin wagging. You cannot curb people's tongues anyway; such is human nature. The Bible says: "A prophet hath no honor in his own country."

Actually I could understand these people. An acquaintance of mine once said to me: "Perhaps Russia has too many talented people to really value them. Hundreds of thousands of such people are now living in villages and regional centers planting potatoes, watching over their grain barns and getting drunk on vodka. They could be excellent cosmetologists or chemists, but they would have to go to a big city, preferably Moscow, to develop their talent. However, to live there you need a permit, which is next to impossible to acquire. This is why gifted people live on the periphery of the country. Our country doesn't need them. What it needs is mediocrities, standardized folk. Standard buildings, standard clothes and wages, hackneyed thoughts and standard behavior. Everyone is content and equal. They are easier to govern that way. In Russia people survive not because of the state, but in spite of it. If the great scientist Lomonosov had not come to Moscow, he would have remained a swineherd for the rest of his life."

My acquaintance was right in many respects. Living in a small town I saw how many bright people took to drinking to drown their anguish. Their unneeded energy was spent wastefully on gossip, petty intrigues, useless effort and fits of motiveless rage...

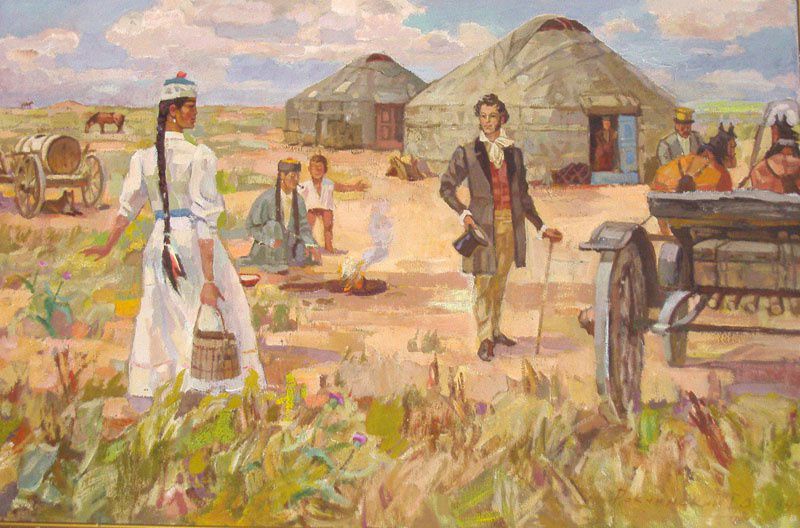

When you ride in the summer steppe for many hours and the monotonous landscape begins to lull you to sleep, sometimes, quite unexpectedly, a bewitching mirage appears before or besides you in the web of the transparent air. Then reality and imagination get mixed up and you are unable to distinguish where dreams begin and reality ends because the borderline between them has seeped.

It is said that a butterfly once appeared to the ancient Chinese philosopher Chuang-tse in his sleep. When he awoke he started to reflect on his dream trying to understand whether it was he who had seen the butterfly or the butterfly who had seen him. So what is reality? Are dreams real, or is reality perhaps nothing but a dream?

Several years later, when our country was undergoing radical change, I remembered how clearly I had sensed the future advent of a reformer.

The day came for me to fly to Moscow to take the entrance examinations. On the way to the airport I spotted a seagull from the car window. It was circling above the steppe. There was nothing unusual about this, for Kalmykia is situated on the ancient seabed of the Caspian Sea, so the age-old instinct of these birds makes them fly far into the remotest parts of the steppe. Like harbingers of times long past, they fly low over the sunbaked land issuing plaintive throaty cries when they cannot find the erstwhile nests of their ancestors. That morning I felt as if I was seeing these sea birds for the first time and an acute anguish gripped my heart. I took a deep breath, smelling the thick, herbal aroma of the steppe and the salty hot air, and then dived into the spacious belly of the airplane.

I was at the beginning of yet another stage in my life. What was awaiting me? How would Moscow - a bustling city burdened with its own problems and concerns, unforgiving of failure, and filled with pride for its fussy and gaudy life-style - greet me?

The plane taxied along the runway, then stopped. Minute later the engines set up a deafening roar, and a shiver ran down the YAK-40's metal body as it raced along the strip of concrete. I was looking through the window. Down far below was my home town with its unpresentable and squat one or two-story houses, a town that had rolled itself into a ball like a stray kitten. Suddenly I was overcome by an acute sense of pity and love for my home. My heart filled with light and a piercing yearning which did not leave me until I reached Moscow...

Much to my surprise I was effortlessly accepted into the institute and became a student of Japanese. However this did not make me feel especially happy. On the contrary, I was a little dissatisfied and disillusioned. For everything turned out to be very different from how I had imagined it.

After the years in the army and at the factory I had a big thirst for knowledge and pounced on books with great enthusiasm. The chief political institute in the country was essentially intended for young men aspiring to big-time careers and a place at the top of the Party hierarchy. I must do the students credit, however, for whenever they set themselves a goal they did their utmost to achieve it. The FRI made it possible for them to live abroad officially, which was one of the shortest routes to the top. Small wonder then that the children, grandchildren and close relatives of the Communist Party elite studied there: Gromyko's grandson, Brezhnev's grandson, Shchelokhov's son, every one of them a "white bone". The institute was also filled with the privileged youth of other Soviet republics and socialist countries - the secretaries of regional party committees, district committees and general officers.

lt was only natural that a circle should form around these so-called "golden youths" in the FRI student body. Many behaved obsequiously and literally danced attendance on them, trying to make friends with the scions of powerful families who were "doomed" to getting the most enviable job placements. As a matter of fact, quite a few among the patricians were rather decent and likeable fellows; they had their faults and flaws (but who doesn't?) and their strong and weak points. So the commoners often pestered the chosen few, trying to curry favor with them by going out of their way to be helpful whenever possible. But there was nothing special about this. Obsequiousness had been cultivated since the very birth of this country. Officially they called it "a devotion to the cause of the Party and personally to..." "Personally" was preferable and valued more highly because not everyone was admitted to the sweet and nourishing class of prominent individuals.

The residents of the steppe used to call the Kalmyk nobility "tsagan yasn", literally "the white bone", or the cream of society. And although the khans and noyons were exterminated along with the clergy, the people of Kalmykia never forgot either the term tsagan yasn or the people whom it represented. However, nature does not tolerate a void, even under socialism. So people gave that name to the Communist Party bureaucrats, the top rank administrators, and the tsagan yasn were born anew.

The residents of the steppe used to call the Kalmyk nobility "tsagan yasn", literally "the white bone", or the cream of society. And although the khans and noyons were exterminated along with the clergy, the people of Kalmykia never forgot either the term tsagan yasn or the people whom it represented. However, nature does not tolerate a void, even under socialism. So people gave that name to the Communist Party bureaucrats, the top rank administrators, and the tsagan yasn were born anew.