Just as I was beginning to feel again that nothing, but nothing ever happened in our country, something did begin to happen. A t that time there was a popular saying that when they start trimming fingernails in Moscow, people in Kalmykia lose their fingers.

We began to feel the effects of the Communist Party's so-called "historical" decisions. The celebrated black earth of our cattle-breeding republic, with its rich grassy pastures where farmers had been grazing sheep as well as cattle for centuries, was plowed to make room for cereals. Our old people warned us that to do such a thing would be disastrous, but the big brass did not listen. In the regional Party Committee, meetings they brutally berated the elders, shouting: "Who do you think you are? Do you consider yourselves cleverer than the authorities in Moscow, huh? ls that why you come out against the decisions of the Party? Tell us your names'?"

In these circumstances anybody would surrender. Nobody relished the prospect of returning to Siberia. So the elders stopped fighting the Party officials. The thin layer of black earth was pierced by the plow, exposing the sand which lay below; sand began to encroach on more and more land.

First rare grasses and herbs were destroyed, and then the indigenous population of wild animals followed. Adverse winds buffeted the steppe, causing great damage to the fragile balance of the ecosystem.

St John's Revelation reads: "One woe is past and, behold, two woes followed." Another historical decision was implemented like a bolt from the blue: the creation of the Volga-Chograi canal interrupted the age-old migration route of the saigas. Countless numbers of these ancient beasts perished in a grave hundreds of kilometers-long. The steppe suffocated with the stench of rotting carcasses. Again they sang in the regional Party Committee meetings: "C’est la lutte finale"..."This is our final battle ... And we will fight to the last man in our struggle''.

They sang this revolutionary song beautifully with one voice. But then how could it be otherwise? A word of dissent and you r were a goner, crawling back to your lair to die from that final and decisive heart attack. When I hear today the outraged voices of the older generation berating the vandalism of the you ng who destroy historical monuments and sculptures, and set churches a light, I think to myself what did you expect? Was it not your generation who blew up the Cathedral of Christ Our Savior in Moscow, which had been built with contributions from the entire nation as ordinary people donated their last penny? Was it not you who turned churches into warehouses and cow-sheds? Did not your generation dynamite and flatten the unique Zhiguli Hills? How do you account for the pollution of Lake Baikal with industrial waste? Was there a corner of the Soviet Union that was not trampled underfoot by the heavy boot of Social ism? No such place exists.

I have heard that in ancient China the emperor would test all his ministers by sending them away from Beijing to spend several years in the provinces. If, when the time came to recall the man, the people of that province did not howl in protest, then he was publicly flogged. Had such a law been in force in Russia then I believe that there would have been many vacancies in the upper echelons of power.

Like all of my generation, I went through several stages of ideological indoctrination aided by extensive state censorship. First I was an Oktyabryonok (a pre-pioneer), then I became a pioneer, progressing to the Young Communist League, and finally becoming a member of the Communist Party. I also served on the pioneer squad council, the Young Communist League Committee, and I was chief of the "Vega" Young Communist League city squad. For many years I lived as though I were drugged; it was only gradually, layer by layer, that I began to peel away at the truth.

I wanted to do something worthy and important for my country. I wanted to feel needed by my homeland. Perhaps this was just a small town boy's longing to be special, but that is another story.

I look back on the past and recall all the offices to which I have been elected. This might have been the starting point, the springing board from which I was to launch my career as a Party apparatchik. Many chose the well-trodden and tested path of the Higher Komsomol School (HPS) and the Higher Party School (H PS), before scaling the heights of first the Regional Party Committee and then the Central Party Committee; only membership of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party then lay between a man and the Soviet Politbureau.

This path, in a word, spelt power: limitless, typically Russian power which even the tsars might have envied. But that was not for me... At the time I was not yet able to understand this myself, for I lacked education and sensitivity. Yet. I felt quite clearly that all this was alien to me.

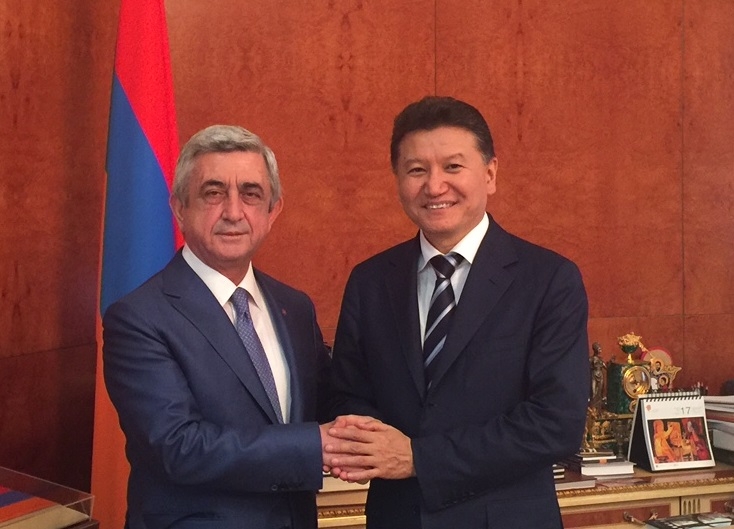

Kirsan Ilyumzhinov

The President's Crown of Thorns, 1995

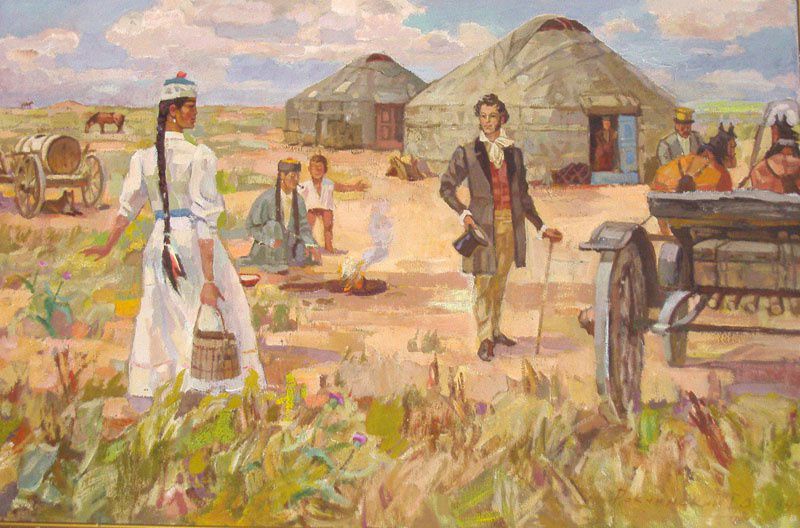

I read our mighty epic "Jangar" and I felt as though I had stepped onto firm ground for the first time; I was immensely proud of our small nation. I began to feel at one with this barren land. I learned that Kalmyk folklore I s second only to that of India in terms of its richness and imagery. l looked on my homeland from a new perspective and began to view our wind -blown, dusty township swept by the sands and snows of the steppe in an altogether different light.

I read our mighty epic "Jangar" and I felt as though I had stepped onto firm ground for the first time; I was immensely proud of our small nation. I began to feel at one with this barren land. I learned that Kalmyk folklore I s second only to that of India in terms of its richness and imagery. l looked on my homeland from a new perspective and began to view our wind -blown, dusty township swept by the sands and snows of the steppe in an altogether different light.