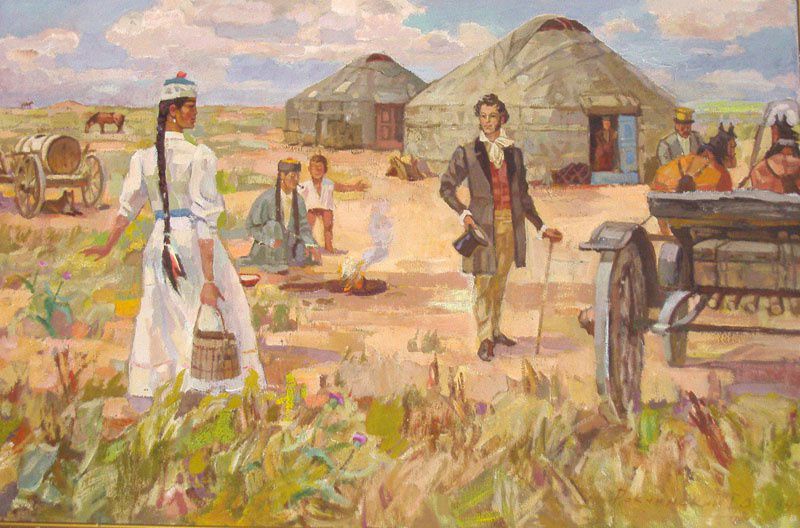

No wonder there is a monument in Elista of the favourite comic character of Kalmyk folklore - old man Keedya. All this old man had was a red shabby sheep. However, wisdom, ingenuity and knowledge of human nature helped him to trade it for seven camels, fur coat and a horse. Even today, choosing a new place for a pasture, shepherds ask old people to bless it after arranging a special dinner for them. They do it not from idle superstition but because an experienced person can see what a shepherd may not notice and the chosen place might not be the right one. More recently, in Soviet times, managers of different levels were forced to dismiss people with invaluable life and production experience. Soviet law was adamant: once you reached a certain age you should leave and enjoy "well-deserved rest".

Many of those who were so kindly dismissed could not get used to redundancy in their new life. And on the street I grew up, there were several of those who felt that they had been thrown away like an old shoe. Literally, six months after strong and vigorous old people were dismissed they lost interest in life and passed away.

Those who, on the contrary, somehow managed to hold on to their business or were carried away by a new one showed and still show the wonders of longevity. My mother Rimma Sergeyevna, God bless her, is already 85 years old but she continues to work as a veterinarian. Moreover, she manages to seriously engage in her hobbies: next to animals, she loves flowers most of all. Her flowerbed, which she made according to all rules of flower arrangement in our Elista house, is admired by such a connoisseur as the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia Alexy.

My father, Nikolai Dordzhinovich, as I already mentioned, found himself in literature. In his essays and novels "Abil", "In the Land of Taiga", "Bitter Years’ Bread", "Soldiers' Fates," he writes about what actually happened in his life: war, deportation, joyful return to homeland, which only a few made, and about the difficult post-war years.

Of course, during Soviet times, a person who occupied responsible posts was forced to keep his thoughts and experiences to himself. Now my father is 89 years old, but he is still active. He works at the republic foundation of war and labour veterans and he still writes much.

On the other hand, I understand those who dream of the time when they no longer would have to go to the hateful work. Once, I had an acquaintance who dreamed of becoming an artist but, following the family tradition, he became an engineer. And although he was one of the best in his office and well paid, I cannot say that he was an absolutely happy person. All our conversations eventually ended with the topic: “I’ll retire, take a sketchbook and spend the whole summer on Volga!”

But, of course, some people are happy with porch chats and endless dominoes tournaments (although I would recommend chess-tennis – a combination of chess and ping pong). Well, all people are different and for some rest and relaxation is a panacea for all diseases.

But I don’t see myself like that if I retire. There are many projects, many interesting things to be done and there is always something becoming more imperative and urgent. Something that makes personal dreams not so important.

Thus, when I "retire", having neither urgent obligation nor pressing cases, I will surely engage myself in long time deferred self-realization. What will I do exactly? I'll tell you later.

I will try to tell you what I think about people over 60 and even over 50. I think this is the best age for self-realization. This is essential feature of my family. My parents are still working. Although I cannot blame those who like to enter their old age sitting on a bench playing dominoes or chess.

I will try to tell you what I think about people over 60 and even over 50. I think this is the best age for self-realization. This is essential feature of my family. My parents are still working. Although I cannot blame those who like to enter their old age sitting on a bench playing dominoes or chess.